In his book [Jaron Lanier](https://en.wikipedia.org/ wiki/Jaron_Lanier) claims that the information on the web is undervalued and underpriced.

According to him this is hollowing out the middle class because people aren’t being sufficiently valued for their information-producing work, while a new rich elite is making vast sums of money by collecting and analysing this cheap information.

In many cases the information being collected and analysed is given freely to companies by the users themselves in return for email, calendaring and social networking features.

This results in information assymmetry (e.g. who knows what about whom) and therefore a large disparity in power and wealth. Google knows everything about you and yet you know nothing of value about Google.

Siren Servers

These online services are hosted on servers, which Lanier has termed Siren Servers1, after the Sirens of Greek Mythology. The Sirens are beautiful but dangerous creatures who lure nearby sailors with their enchanting music and voices, thereby letting them shipwreck on the rocky coast of their island.

These Siren Servers lure us into opening up our lives, so that they might freely gather data from us, on a truly massive scale, which they then analyse and profit from.

The results of this analysis is ”kept secret and used to manipulate the rest of the world to advantage.”

So much value is extracted from this data, that these Siren Servers are valued in the billions of dollars.

Lanier claims that the users of these servers are shortchanged, in that they don’t get their data’s worth in return. Not to mention the broader societal damage wrought by the surveillance-as-business-model engendered by this approach as well as the decimation of the middle class as software takes over many industries.

Siren Servers reduce risk for themselves, but in the process increase the risk for all the other smaller players. Uber’s business model for example is all about shifting risks onto its drivers. They would not be profitable if they had to carry the costs of commercial insurance, licensing, vehicle maintenance and oversight of drivers.

”The total amount of risk in the market as a whole stays the same, perhaps, but it’s not distributed evenly. Instead the smaller players take on more risk while the player with the biggest computer takes on less.”

Lanier’s solution to the emergence of Siren Servers is to “properly account” for the wealth created by people online. In other words, people need to be paid for what they do online, no matter how small and seemingly insignificant.

”If information age accounting were complete and honest, as much information as possible would be valued in economic terms. If, however “raw” information, or information that hasn’t yet been routed by those who run the most central computers, isn’t valued, then a massive disenfranchisement will take place.”

The decimation of the middle class

Lanier says this process started in the creative industry, with musicians and photographers impacted quite early on, and that it’s now spreading to other occupations, such as travel agents, estate agents and journalists.

Lanier writes:

”Making information free is survivable so long as only limited numbers of people are disenfranchised. As much as it pains me to say so, we can survive if we only destroy the middle classes of musicians, journalists and photographers. What is not survivable is the additional destruction of the middle classes in transportation, manufacturing, energy, office work, education and health care. And all that destruction will come surely if the dominant idea of an information economy isn’t improved.”

In other words, until we reconfigure the economic system to value raw data by compensating the people that generate it, we will have massive inequality.

Not everybody is of course as pessimistic or draws these same conclusions. Steve Albini, producer of Nirvana and Pixies albums and himself a touring musician, says in this keynote that the Internet has solved many problems for musicians and audiences alike and that things are actually better now than before.

Finance got networked in the wrong way

As an example of the destruction being wrought by the Siren Servers, Lanier asserts that the Great Recession was in part caused by their existence in the financial sector.

”Consider the expansion of the financial sector prior to the Great Recession. It’s not as if that sector was accomplishing any more than it ever had. If it’s product is to manage risk, it clearly did a terrible job. It expanded purely because of its top positions on networks. Moral hazard has never met a more efficient amplifier than a digital network. The more influential digital networks become, the more potential moral hazard we’ll see, unless we change the architecture.”

It’s clear that Lanier believes that this problem can be solved by reconfiguring and improving the architecture of our digital networks.

Siren Servers and the rise of surveillance as a business model

As has become increasingly clear in the past few years, the dominant business model in Silicon Valley is one based upon surveillance.

Surveillance is the mechanism by which the Siren Servers gather much of the data they analyse and profit from.

According to Lanier, many Silicon Valley techno-libertarians handwave any concerns about corporate surveillance.

”Surveillance by the technical few on the less technical many can be tolerated for now because of hopes for an endgame on which everything will become transparent to everyone. Network entrepeneurs and cyber-activists alike seem to imagine that today’s elite network servers in positions of information supremacy will eventually become eternally benign or just dissolve.”

However, what good reason is there for owners of these immensely powerful and valuable Siren Servers to one day willingly become transparent and open up in order for this power imbalance to be resolved?

On the supposed emergence of some kind of sharing/socialist utopia arising out of the aggressive right-wing libertarian practices of Silicon Valley, Lanier mocks:

”Free Google tools and free Twitter are leading to a world where everything is free because people share, but isn’t it great that we can corner billions of dollars by gathering data no on else has?” If everything will be free, why are we trying to corner anything? Are our fortunes only temporary? Will they become moot when we’re done?”

These ”network servers in positions of information supremacy” hide their code and algorithms behind patents, IP-laws and copyright.

A whole legal facade has been erected precisely to prevent the hopeful scenario of “elite network servers” dissolving into an utopian abundance.

Lanier’s proposed solutions

Cyber-keynesianism

Lanier describes his proposed solution as a sort of Cyber-Keynesianism. Based upon the idea from the economist J.M. Keynes that “stimulus” might be able to kick an economy out of a rut.

Lanier provides a qualitative explanation of the stimulus theory which I haven’t heard before.

On a multi-dimensional mathematical landscape (as could be plotted based on the parameters of an economy), there are peaks and valleys. Let’s assume that peaks are “optimal” economical configurations, where the greater good is best served, and valleys are horror scenarios (depressions, recession, collapse etc.).

Not all peaks are of equal hight, and when you are on a peak, you are usually surrounded by valleys. There might be a higher peak (i.e. better configuration) available, but it’s not clear how to get there, since moving there might mean moving through valleys.

The idea behind stimulus is to provide the impetus, a kick if you will, to make this transition to a higher peak.

Technical Solution

Laniers solution on a technical level is to use a network with bidirectional links, instead of unidirectional links as we currently have with the web. The architecture of this network is inspired by Project Xanadu already founded by Ted Nelson in 1960.

Whenever someone publishes something on the web they would be informed if someone else links to their work, due to the bidirectionality of the links. This would supposedly put a stop to copyright infringement and also allow content creators to correctly identify and bill the consumers of their media.

Of course, this would only work if there were no anonymity on the web.

Lanier further proposes a single, public, digitally networked marketplace where every participant is tied to his personal real-life identity, and where anything anyone creates online has to be paid for.

My Criticism

I thoroughly enjoyed reading Lanier’s analyses, and his descriptions of the mechanisms behind Siren Servers in particular. This was for me the best part of the book.

However, he often hand-waves obvious counter arguments or advances his own arguments in a non-rigorous way, often relying on personal anecdotes.

Digital networks’ supposed role in hollowing out of the middle class

Considering his central thesis, that digital networking is hollowing out the middle class in developed societies, I’m not sure how much blame for that can be assigned to digital networking. Other plausible factors include demographic change, globalisation and the money printing policies of Central Banks which are fueling asset price bubbles while real wages remain stagnant, thereby making wage-earners poorer.

My expectation is that no particular factor can be singled out, and that the causes are multiple, varied and intertwined in complex and difficult to understand ways, precisely because the economy is a complex, chaotic system (in a mathematical sense).

Lanier fails to meaningfully address Free and Open Source software

Lanier only very superficially addresses the role of free and open source software (FOSS) and doesn’t even mention (let alone extensively cover or deconstruct) the ideology of Free Software at all.

As a quick recap to people who don’t know the difference between “Free Software” and “Open Source software”:

Both groups concern themselves with creating software where the source code is visible, as opposed to software where you cannot inspect the source code, and are therefore unable to modify or know what it is really doing.

“Free Software” (as in freedom, not price) however stresses a moral and ethical dimension of software development and usage. It basically boils down to the fact that non-free software creates a dangerous and immoral power imbalance, slanted in favor of the creator of the non-free software and against the user of that software.2

Open Source software on the other hand ignores the moral dimension completely and takes a much more expedient approach. It simply asserts that developing software in the “open”, in other words, with the source exposed, is a superior form of software development which will result in better code.

In the index of this book, there is no entry for “Free Software” or “Open Source Software”. There is one entry “open source applications”.

Lanier doesn’t even attempt to address the viewpoint of the Free Software movement, which has been warning about these issues (structural power imbalance, Siren Servers, ubiquitous online surveillance) for decades. This is in my opinion a glaring omission from the book.

Lanier might have coined the catchy phrase Siren Servers, but his analysis of their role and negative effects on users and society might have well come from someone from the Free Software movement. See for example the article Who does that server really serve?.

As the saying goes, ”There is no cloud, only other people’s computers”3

Lanier of course, comes to a completely different conclusion on what needs to be done to resolve the situation, and appears to hold proponents of Free and Open Source Software (dimissively calling them “racals”, “openness crusaders” and Pirate Party types), not only in contempt, but partly responsible for the emergence of Siren Servers and rise of surveillance as business model.

It is clear that if Lanier were to meaningfully address all ideological opponents of his vision for the future, then he would have had to address the ideas behind Free Software in a methodical and rigorous manner and not with dismissive hand-waving.

The fact of the matter is that Free Software does provide an alternative solution to the current mess of online surveillance, increasing risk and fragilization, extreme power imbalances and centralization into Siren Servers.

The solution is to ensure that the software you use is free. If software being used by a service is free and issued under a license that ensures its freeness](https://www.gnu.org/licenses/why-affero-gpl.html), then that server will not have the ability to eventually become a Siren Server.

The reason for this is that users will know exactly what the software does with their data and will have the ability to switch to a different provider (while taking all their data with them), or to host it themselves, at a moment’s notice.

This means that the power balance is no longer slanted in favor of the service provider, and users are much more in control of their data and content.

Lanier’s hypocrisy

Throughout the book, Lanier criticises in particular Google and Facebook for their creepy surveillance business models and their usage of Siren Servers.

Lanier himself works for Microsoft, a company that is feverishly competing with Google and Facebook in surveilling users and in establishing their own Siren Servers.

However, Lanier of course does not at all address this conflict of interest or that fact that his employer is just as complicit as the companies he calls out. This apparent hypocrisy severely detracts from the integrity of his book.

Lanier’s superficial and misconstrued criticisms of “openness”

Lanier’s refusal to meaningfully engage with the different ideas and philosophies behind what he calls “openness” is for me one of the most disappointing aspects of the book.

Wikipedia

He deceptively equates Wikipedia and Facebook, saying that both are a culmination of the “information should be free” meme and that both contribute to the devaluation of user created content. In a previous book, he even calls Wikipedia “Digital Maoism”.

Wikipedia is concerned with creating a digital Commons. By voluntarily contributing to the commons (as Wikipedia contributors do), you are not devaluing your work, you are making it priceless, in both the literal and figurative senses of the word.

Conversely, the information on Facebook is not free and is not part of a commons.

I find it good to know that there are some things in this world on which one cannot put a price tag, despite the efforts of people like Lanier.

As the saying goes. ”A cynic is someone who knows the price of everything and the value of nothing.”

Wikileaks

Lanier incorrectly claims that Wikileaks is concerned with abolishing all privacy. Anyone who has made even a half-arsed effort to understand what Wikileaks is about would know that they stand for transparency of the powerful and their institutions, in order to keep them democratically accountable, and that they don’t advocate the elimination of all personal privacy.

Of course, this is a common mischaracterization of this organization, often done to intentionally discredit them. Either Lanier is also trying to discredit them or he couldn’t be bothered to properly research their stated goals.

Linux

Lanier claims: ”A linux always begets a Google” as if it’s is somehow responsible for the emergence of Siren Servers. This doesn’t explain Siren Servers built upon proprietary software, such as StackOverflow which uses Microsoft.

Inasmuch as one could argue that Siren Servers are the result of open source software (note the distinction) it is exactly due to open source’s gutting of the moral aspect out of free software.

Lanier wants to remove anonymity on the web

Lanier criticises tech companies for their creepy surveillance business models, and yet his proposal for “fixing” the internet would eradicate all privacy online and have all human interactions facilitated via a single, public market place. It would be a surveillance and privacy nightmare.

Concerning anonymity on the web, Lanier says this is the result of the “pot-smoking liberals” and “paranoid conservatives” who originally built the system and who thought anonymity was “cool”. Such a perfect example of his dismissive, non-rigorous and arbitrary reductionism which completely fails to meaningfully confront the potential benefits or dangers of anonymity on the web.

Lanier completely fails to address the fact that anonymity is often the only defence people may have against corrupt and malevolent state power. Whether this applies to activists during revolutions or to conscientous whistleblowers, doing away with privacy would be throwing away one of the few ways of ensuring free speech online.

Monetizing all human interactions debases them

By wanting to turn the web into a giant marketplace where everyone operates with an exposed identity and every digital creation, no matter how trivial, needs to be paid for, Lanier wants to further the already ongoing monetization of the public commons. As Charles Eisenstein writes sacred economics, monetizing all human interactions actually debases them.

Lanier calls his approach “humanitarian”; it is anything but. Instead, by monetizing and thereby commodifying every online human interaction, whether it’s a joke, a compliment or a statement of support, these interactions are stripped of their inherent sacred quality of humanity.

If you know that someone who sends you a message of support or love will receive a micropayment for that message, could the original intent of the message not be called into doubt?

My proposed solutions

It’s about freedom, not cost

Lanier’s proposed solution ultimately has to do with costs and trying to find a way to get people paid for anything they write and then publish online, no matter how trivial.

However, in so doing he comes up with a proposed solution that does away with all privacy and anonymity.

His proposal of using a network with bidirectional links might threaten the Siren Server status of services such as Facebook and Google. However, it’s not clear how such a network will solve the problem of Uber or AirBNB becoming Siren Servers, thereby pushing out the middle class jobs of taxi drivers and guest house operators.

It’s not only about the network architecture, as Lanier suggests. What’s more important is Software and Computing Freedom.

If you don’t have the freedom to study, use and modify the software that you use, then you will be systematically exploited and preyed upon, no matter what the network architecture looks like.

Free software specifically, is defined by these four freedoms:

- The freedom to run the program as you wish, for any purpose

- The freedom to read the source code and to modify it as you wish.

- The freedom to redistribute original copies so you can help your neighbor.

- The freedom to distribute your own modified copies to others.

Being able to read the source code is essential for software to be free. An organisation is however only compelled to share their source code if they intend to distribute compiled copies as well. If the software is used privately, i.e. in-house, then they are under no such obligation.

Open Source on the other hand, also gives the right to read the source code, but many open source licenses do not ensure the last two freedoms, and therefore offer weaker protection.

There is however a large overlap between the two groups. Most open source software is also free software, and vice versa.

Free software coupled with free and open protocols means that users are not beholden to specific service providers. It’s exactly this aspect of it which is why the dominant tech companies avoid free software like the plague and instead embrace the watered down notion of “open source”. Their goal is to maintain strict vendor lock-in, making it difficult for users to switch to other service providers by holding their data and online personas ransom. Something which they could not do if their software respected the above four freedoms.

Who pays for fee software?

When discussing free software, the question often arises how one should make money with software if you cannot enforce artificial scarcity, vendor lock-in, holding user’s data ransom or spying on them.

This is perhaps a topic for another blog post. In short, it definitely is possible to make money writing freedom respecting software and the more people insist on using only free software, the more economic opportunities will arise.

Software is better seen as a living, changing and evolving ecosystem, than as a static object. It needs constant care and attention, to keep it relevant, accurate, applicable and functioning. This care and attention is a service which can and should be paid for.

Who pays for this service? The users do. Whether they are governments, universities, corporations or private individuals.

How do they pay for it? Organisations sign service and support contracts. They also commission the writing of new features or entirely new applications.

Private individuals can pay for free software through crowdfunding, bounties, and donations.4

Public institutions and foundations can issue grants or fund the development of free software for usage in government and publically owned enterprises.

If all governments decided to only fund and use free software, it would create a massive amount of investment in the sector. Additionally, money spent on developing free software can be invested in a country’s own programmer workforce, instead of it being sent overseas to oversized foreign corporations.

However, those companies that currently spy on us, hold our data ransom and restrict our digital freedoms, won’t change by themselves. It’s up to the users to take matters into their own hands, to demand freedom and to support those companies, organizations and people who develop free software.

Decentralization

The problems Lanier identify are largely caused by data-assymetry (who has data on whom) and the resulting siren servers.

An architectural approach to solving this problem, which complements free software, is decentralization.

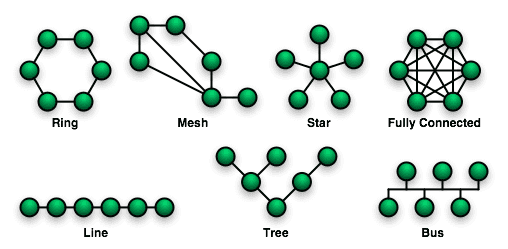

Decentralization refers to a network structure (called topology) where each node in the network can connect directly with any other node, without the intervention of a middle man (such as Facebook or Google).

In the network topologies pictured here, the fully connected topology is the most decentralized, while the star network is the most centralized.

Creating large decentralized networks is more difficult than creating centralized ones, which is why the web has come to rely on centralized Siren Servers to such a large degree.

However, much exciting work is being done on decentralizing the web and putting people back in control.

Consider Finance, and Lanier’s assertion that Siren Servers contributed to the financial crisis preceding the Great Recession.

It’s more difficult to have a financial Siren Server when financial data is decentralized and therefore effectively available to everyone.

This is already the case with decentralized cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin. The bitcoin protocol is an open and free protocol, the original bitcoin wallet is free software and the transaction information contained in the blockchain is available to all.

An improvement upon Bitcoin would be to allow truly anonymous transactions, and this appears to be on the horizon.

Bitcoin and cryptocurrencies are however only one application which can be built on top of the revolutionary distributed consensus blockchain technology upon which it rests.

There’s already work on distributed cloud hosting, distributed microblogging and a myriad of other services running in a decentralized (non-Siren Server) manner.

Federation

An older idea than blockchain-based decentralization is federation. Think of the way in which you can send an email from a Gmail account to someone with a Yahoo account, or to someone who hosts their own mail server.

Why can we send email to people with different service providers, but we cannot send chat messages from a Google account to an iMessage account, or between Whatsapp and Yahoo messenger?

This ability of email is the result of something called federation. The ability of servers from different providers and with different implementations, to communicate and relay messages between one another.

Email is federated but facebook messages are not, because you cannot send a facebook message to someone outside of facebook.

There is no technical reason why instant messaging cannot be federated. In fact, XMPP, the protocol on which many of the messaging services are originally based, allows federation.

The reason we don’t have federation in messaging is because it’s not in the interest of Siren Servers. It would actively undermine their dominance.

If any of the big email providers, Google, Yahoo, Microsoft or Apple, could get away with only allowing emails within their own system, they would have done it by now. The proof is in the fact that they actively prevent federation in their messaging apps. The reason they cannot do it with email is because federated email achieved critical mass before any single company could kill it off.

Unfortunately, this was not the case with instant messaging. Therefore, if you actively want to work against Siren Servers, you should only use instant messaging servers which support federation, such as XMPP.

You can sign up for a free XMPP chat account here. And if you’d like to chat with me, add me as a contact:

Conclusion

As you can see, I believe in a completely different remedy than the one which Lanier suggests. One that’s based on a methodology, legal framework and software which is already being used instead of something which Wired magazine in 1995 called the longest-running vaporware project in the history of computing.

I thoroughly enjoyed Lanier’s analyses and his unique perspective on things which I think made the book worth reading.

However, his non-rigorous approach, his dismissiveness or ignorance of alternative narratives and approaches to resolving the issues he mentions, as well as his hypocritical omission of his own employer’s complicity, left me disappointed and uninspired.

Footnotes:

Introduction to Free Software and the Liberation of Cyberspace

- Bruce Sterling calls them “The Stacks”, vertically integrated social media. See Bruce Sterling At SXSW 2013: The Best Quotes.↩

- If you’re interested in more detail about Free Software, watch this presentation by Richard Stallman:↩

- The earliest reference to this that I could find, is this article↩

- See Kickstarter, IndieGogo, Startjoin, Patreon, Bountysource, Gratipay and Snowdrift.↩

Hello, I'm JC Brand, software developer and consultant.

I have decades of experience working with open source software, for governments, small startups and large corporates.

I created and maintain Converse, a popular XMPP chat client.

I can help you integrate chat and instant messaging features into your website or intranet.

Don't hesitate to contact me if you'd like to connect.